I was once trapped on a brief tour of the UK with a bunch of ego-inflated and seemingly troubled well-known musicians, having been lured there under the false pretenses of them needed a banjo player for their ‘Super Group,’ but then upon arrival in Manchester told by the bass player I wasn’t famous enough to share the stage with them. The 23-year-old tour manager offered payment and free guest spots for my friends if I stayed on just to help out with production and I stupidly agreed. What followed was a week of spirit-crushing hell of almost comic proportions, and ever since I’ve tried not to speak about it too much, mainly out of concern for my blood pressure.

However.

One morning hurtling towards Glasgow in an awkwardly silent packed van I was stuck sitting between a couple of the musicians who seemed to be trying to blot out my very existence to the point of not even answering when I asked them questions. I gave up trying and just put on my sunglasses and felt homesick. We stopped for fuel and toilets at a petrol station and all piled out and listlessly ambled through the automatic doors single file. Just as I’d stepped inside a grey-haired man wearing an earring stopped me on his way out.

“Darren?” he said, “fancy seeing you here!” and before I could reply he embraced me heartily.

At first I was startled but once released, I was able to get a good look at him and claim recognition.

“Mac!” I said, “What a surprise! What are you doing here?”

“We’re on our way to Glasgow for a show,” he said, “But more importantly, what are you doing here all the way from Australia?”

“It’s a long story,” I told him vaguely.

I felt embarrassed to tell him I was now just lugging and selling merch for these people, I could see them all loitering around the confectionery racks watching me curiously.

We talked for a bit, and each gave an abridged 5-minute version of the past two or so years of our lives, and I promised to send him my new album.

“Well, it’s great to see you, the car’s waiting, I’d better go,” he said and walked out onto the forecourt, but then came back to say, “Oh, we’re having a party tonight after the show. You should come, and bring your friends.”

He gave me the details and then was gone.

–

Back on the highway the mood in our van had shifted towards a kind of pregnant anticipation, all eyes seemed to be on me: the sudden curio. Finally someone broke the ice and in a tone of frustrated defeat asked, “Who was that you were talking to?”

“Oh, that was Ian McLagan,” I said with as much nonchalance as I could muster, “He used to play keyboards in the Small Faces. Do you know him?”

“Bullshit!” someone yelled from the front passenger seat.

“I’m afraid it was him,” I said, “He’s got his own band these days. The Bump Band. He’s playing Glasgow tonight too. Check the gig guide.”

“Then how do you know him?” someone else asked.

“Well I toured with him. I’m a working musician too. He used to play in Billy Bragg’s band. We went around Ireland together. And I see him sometimes when he comes to Australia.”

“Holly shit,” my questioner muttered to himself, “Ian McLagan…”

Yet another band member piped up from the back seat stuttering, “Oh wow… He’s actually my neighbor in Texas, he owns the ranch next door! I’ve never actually been able to meet him though.”

“Well, he’s having a private party tonight in Glasgow,” I said, and for the final blow, “I might be able to get some of you in, but I can’t promise anything.”

–

Even though for the rest of that tour I was regarded with only a sliver more respect, that moment at the Service Station felt deliciously satisfying, like the turning point in an 80s redemption movie. I was the Man From Snowy River, when Clancy of the Overflow came down from the mountains like a God, singling him out and saying, “Sorry to hear about your father Jim. He was a good man,” while all the fawning station workers looked on green-eyed.

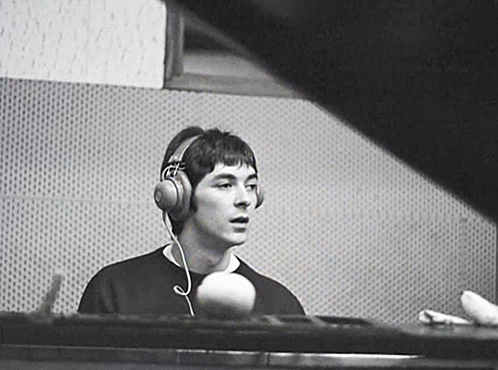

And just like a kind of Rock and Roll Clancy of the Overflow, whenever anyone spoke of Mac, words like “legend” and “gentleman” were thrown about. From the very first day I joined the Billy Bragg tour he went out of his way to make me feel like an equal, even though I was just a lowly support act. Always smiling, always offering a beer off their rider. It became a running joke each sound check as the Bragg band would run through a new arrangement of ‘A New England,’ when towards the end of the song they’d all stop for a 4-bar breakdown and Mac would point and yell my name and I’d play the riff on the banjo sitting alone in the empty auditorium.

I remember him laughing when I told him I’d found his autobiography in the ‘Crime’ section of a Belfast bookshop. “Well I certainly got away with murder a few times,” he said impishly, “Musically speaking.”

He seemed more than happy to sit around after shows and indulge us avid listeners with his war stories: buying his precious Hammond B3 organ as a teenager and learning Green Onions on it from a Booker T album; hilarious anecdotes of touring with Dylan in the 80s where they were housed in European castles and Bob getting into the mood a little too earnestly by wearing puffy Lord Byron shirts.

On the last night of the Bragg tour he asked me out to a party in Dublin, but instead I chose to follow a girl to a horrible nightclub. Little did I know as I sang The Fairytale of New York in full-voice with a hundred or so other Irish drunkards when the ugly lights came on, that somewhere across town Mac was holding court at a raging party where members of the Rolling Stones AND the Commitments had turned up and were all dancing, singing and taking photographs with gob-smacked fans. I heard about it all the next day, hung over on a ferry back to England, in lurid panoramic detail off one of the tour roadies and have questioned my judgment every since.

As is often the case in the peripatetic life of the traveling musician, these brief encounters loom large. Much will be written in the coming days of Mac’s musical legacy. But I’d like my small tribute to be to Ian McLagan, the exceptional human being. I had only a handful of nights in his company, but the memory of those reinforce why it’s all worth it: we’re all in this together, so let’s have a good time. What a Gentleman!